Bhutan Journal

Day 1: Transit

Getting to Bhutan is a multi-day experience. It's at least one connection from Boston to Bangkok (we are taking two), and roughly 30 hours transit time. We couldn't immediately travel on to Bhutan, plus you are often encouraged to stop a day to allow for the vagaries and uncertainties of long flights, so we spent a lovely relaxing day in Bangkok revisiting some favorite spots. Our favorite Bangkok hotel is right on the river, with an outdoor restaurant from which you can watch the boats and see the sun set over the city. Always a pleasant resting place, plus it comes with cold beer and Thai food.

The next (very early) morning finds us in a bright pink taxi hurtling toward the airport. This is our first time through since the new airport was opened in 2008 or 2009, and it's really lovely. It is clean, efficient, well laid-out, and as always hospitable. I am particularly entertained by the priority security line that is for 1st class, business, Gold airline status, diplomats … and monks. The only airline that flies to Bhutan is the national Druk Air, which at this writing recently celebrated buying their 3rd plane. They fly daily from BKK with stops in India. Since they have no agreements with other carriers, you have to check in separately. The only way to get a Bhutan visa is via an approved tour agency, and the visa is linked to your air tickets -- no standbys! Our flight to Gaya in India is quiet and boring, and during our stopover we lose a large tour group dressed all in white and gain many saffron-robed monks, some in first class. I hope they have a priority security line here, too.

The landing at Paro is considered one of the scariest and most difficult to learn in the world, and only about a dozen pilots are qualified for it. It's visual approach only, so there are no night arrivals, and flights are delayed at times for a day or more due to fog. After leaving Gaya we had an amazing view of the Himalayas to our left -- Sagarmartha (Everest), Chomolhari, and the rest of the range. We get closer and closer, then dive below the clouds. There are snow-topped peaks to either side as we gently descend. Then the snow disappears and we see farms, villages, and houses dotting the sides of the hills. The houses are all in the typical Bhutanese style, whitewashed and with elaborate wooden windows. We are seeing them in rather a lot of detail considering we're on a plane. We bank left, skimming the hillside. Then right, wending our way through narrow valleys, ever dropping. Just when you start to wonder if we'll be picking up a stray cow on the wing, we level out over a narrow river and then land on a short airstrip. It's beautifully done, but you do wonder how anyone ever learns this approach. On arrival our pilot welcomes “Your majesty, ladies and gentlemen...” and we notice a rather large welcoming committee complete with a red carpet. However no one seems to walk down the carpet and the committee slowly disperses. We sidestep to avoid treading on the carpet as we disembark. I wonder what happened -- it couldn't be the wrong flight, there are only two arriving today!

The airport is small but efficient, much cleaner and better organized than most. We can't help but notice that the luggage from our flight includes a lot of boxes of food that are being shipped to various luxury hotels in the country. Amankora alone picks up at least a dozen boxes. As we clear customs we are asked only if we have cigarettes. This is now a non-smoking country, and visitors have strict limits on the number of cigarettes they can bring in for their own use. We are cleared and move on. Interestingly, there is also a move to ban alcohol and the eating of meat. The latter seems likely to work, as there is no tradition of butchery in this Buddhist country, and animals are kept for eggs, cheese, and plowing. All meat is shipped in from India, perhaps in large boxes on planes but mostly in non-refrigerated trucks on tiny mountain roads, so it's a very veg vacation.

We celebrate our arrival by driving to the capital, roughly 90 minutes away. Thimphu is a relatively new city, and has only been the capital since 1961. It is, however, the largest city in the country with about 80,000 residents. Due to governmental requirements that buildings be less than 6 stories high, must be of traditional design, and must use only approved land, the city is spread out along the valley. There is a city centre of sorts, with the national stadium, the archery field, and a number of museums and government offices. This area can be crossed in perhaps 15 minutes, which we proved on our first afternoon. There are further communities, almost like connected villages, with commercial districts their own, but no discernable industrial zone. The city is very clean by developing world standards and the inhabitants are largely in traditional dress. Traffic is not busy but is consistent, polite without the incessant honking typical of India (this car has a horn!). The city famously installed and then removed the only traffic signal in the country at the main intersection; now the traffic circle is once again staffed by a white-gloved policeman.

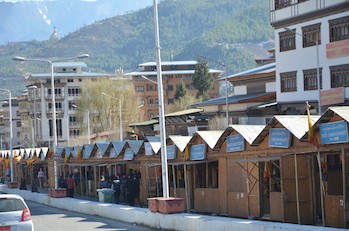

The archery field is the center of attention this afternoon, as there is a some kind of celebration there attended by the king. We go out right as this ends, so people are streaming away from the field and back uphill to their homes. The bunting and banners remain in place, though, and we are able to walk by and peek into the field for a few minutes. Archery is the national sport of Bhutan, dating back to the medieval days of warfare with the Tibetans. Many people have bows and practice, although it's even more common to see a friendly game of darts on any vaguely flat and long bit of land. The Thimphu field is also the location of the Bhutan Olympic committee; Bhutan has sent athletes to the Summer Olympics since 1984, participating only in archery.  As we walk back to the hotel, we see a long series of outdoor stalls that sell handicrafts lined up along the street. This was apparently built for the wedding of the King and Queen last year, but was so popular it remained in place. There are endless stalls selling a rotation of the same goods: modern thangka, woven kira fabric, pressed wooden masks, and embroidered novelty items. The goods seem to be much the same from stall to stall, and although a few have some new items it gets monotonous very quickly. There's nothing that is so unique or so well done that you really feel obliged to buy it; everything is fine but nothing stands out. Things we did not buy while in Bhutan included: gigantic phallus ornaments to hang from your doorway to protect your home, conical funnel hats worn by the Laya tribe, presumably in honor of the tin woodsman, and battery-powered dashboard prayer wheels with LED lighting. We gamely walk the whole way uphill, and at the end Steve promptly dubs it the Bhutan Death Mart. At least there's a general store with Thai Coke at the end.

As we walk back to the hotel, we see a long series of outdoor stalls that sell handicrafts lined up along the street. This was apparently built for the wedding of the King and Queen last year, but was so popular it remained in place. There are endless stalls selling a rotation of the same goods: modern thangka, woven kira fabric, pressed wooden masks, and embroidered novelty items. The goods seem to be much the same from stall to stall, and although a few have some new items it gets monotonous very quickly. There's nothing that is so unique or so well done that you really feel obliged to buy it; everything is fine but nothing stands out. Things we did not buy while in Bhutan included: gigantic phallus ornaments to hang from your doorway to protect your home, conical funnel hats worn by the Laya tribe, presumably in honor of the tin woodsman, and battery-powered dashboard prayer wheels with LED lighting. We gamely walk the whole way uphill, and at the end Steve promptly dubs it the Bhutan Death Mart. At least there's a general store with Thai Coke at the end.

We chose to stay in the rather placial Taj hotel, right near downtown. It seems to stretch the “6 floor” definition and is several times the size of any other building in sight. That said, it has only 60 rooms. We are welcomed with the usual Taj choreography and are shown to a stunningly lovely room with a sitting area, a huge bath, and both satellite Star TV and Wifi. We had been informed of the inevitable local culture dance show at 6pm, and decided to head down for a drink and some dancing. Much to our horror, this turned out to be a private viewing. It was a bit cold out, so rather than light the bonfire outside they shoved some tables aside in the main dining room and did the show there. The dancers outnumbered us 4:1, plus we had several dedicated waitstaff to see to our every unexpressed potential need. Fortunately the singing was actually good; normally we have a rather snide peanut-gallery attitude to watching these shows that simply was not possible. (Overall, I'd score this show about 4 yaks at most, the low score reflecting the general grace of the dancers and the fact the chords were in tune. However, anything that involves repetitive swaying has to rate over 3 on general principles.) I felt terrible that easily 12 people were dragged in for this show for just the two of us. Then again, I suppose they were all paid, which they might not have been if we had opted for a long nap instead? Unclear. For dinner we were shown to a special table right near one of the wood-burning ovens. I was tempted to ask what they had on hand rather than read the menu -- or perhaps find out what the staff was having? -- but the lovely women were so eager to please that you sort of felt you had to pick something. It was very Raj and odd, although extremely tasty. The hotel has two restaurants, and I kept wondering if the entire show would have picked up stakes and moved down the hall if we'd said we wanted to go there. In the morning we discovered that there were two other rooms occupied, but apparently the other couples had other dinner plans. At least we had company for the breakfast buffet!

Day 2: Thimphu to Punakha

Thimphu is the current capital, but for hundreds of years Punakha has been the winter capital and center of religious, administrative, and artistic life. There is a festival ongoing in Punakha and we hope to catch part of it during the day. In the morning, our driver navigates up to Dochu La pass at 3150m. The pass is lightly snow-covered, with a stunning view of the high mountains further north. We are lucky to cross on a clear day when the air is crystalline and fresh. There is a lovely chorten at the top of the pass with many small stupas surrounding a central temple. It's the perfect picture of Himalayan natural beauty, and requires only a short icy climb to capture on film. The other side of the pass is a long, windy road through the forest. The Thimphu side had villages almost all the way to the pass, but this side is mostly national park and is quiet. We descend (in a large S) down to Punakha valley. Steering wheels in this country must take a pounding -- they are constantly in motion.

There is a 3-day festival ongoing in Punakha, held in the courtyard of the Dzong. These gigantic structures are monasteries, temples, and administrative centers for each major valley in the country. They are the center of society and the focus of governance. As an example of their dominance in village life, the official language of Bhutan is Dzongka -- the language of the Dzong -- which is an offshoot of Tibetan. The Punakha Dzong site is hundreds of years old and sits at a strategic confluence of two rivers. The festival is an annual event commemorating a historic battle, but the true value seems to be the excuse for people from all over the valley to come together. The main courtyard of the Dzong is opened; the lama and the monks watch from the gallery, and hundreds of people, all in their festival best, sit happily watching the dances. The masked dancers are particularly graceful, bending and turning with big deer antlers on their heads. That said, it's rather repetitive after a while and it's more fun to watch the crowd. There are clumps of Westerners off to the sides with long camera lenses and varying degrees of dance appreciation. The residents sit happily watching, herding children out of the way and eating oranges delicately. Many of the dancers are known to all and wave to friends as they enter and exit. It's sort of a talent show as well as a celebration, and it feels a bit like the spring show at a local high school.

We leave the festival to explore the rest of the valley, having enjoyed several dances but also noticing a certain similarity in their execution. There is no big town or central settlement, rather small villages dot the hills surrounded by terraced fields. The houses are traditionally of pounded earth, whitewashed, with elaborately carved wooden windows. The white walls are painted with protective deities and symbols, and the carving is highlighted with multi-colored designs on each crosspiece. Each house has a white flag mounted at the center of the roof; this is placed annually as a blessing. Most have crossed phalluses hanging from the corner of the roof as a symbol of the Drunken Madman, a local holy man. The carefully terraced fields grow rice, wheat, and mustard. There are some apple trees and small kitchen gardens, but not much variety of crop.

One of the key sites of the Punakha valley is the temple of the Drunken Madman. This interesting character is one of the key figures of Bhutanese Buddhism, although he does not appear in Tibet or other neighboring countries. The stories of his life consist of various ridiculous and somewhat rude pranks, but always come back to the core tenet that intention and purpose matter more than the surface appearance. These stories are frequent explanations for various traditions throughout the country.

Our hotel in Punakha is nice, if a bit basic. There are about 20 rooms, 4 each in little bungalows, although their numbering convention is mystical. (Rooms 101, 102, 103, and 121 are all in the same cottage; one of these things is not like the other?) They do, however, have an outdoor WiFi pavillion for guests. The cold breeze is only a slight deterrent to the crowds of chattering Chinese and Korean tourists excitedly texting home while enjoying warming teacoffee and bland biscuits. One morning a German grandmother used her iPad to FaceTime her grandchildren, strategically seated with mountains behind her chair. It's incongruous to be in such a quiet, agrarian, and deeply religious country and hear constant iPhone text alerts.

Dinner, like most non-Taj meals, consists of the same 4 or 5 Tourism Board-approved dishes: noodles with steamed vegetables, white and red rices, steamed cauliflower, stewed spinach, and roasted potatoes. Local specialities such as chilis with cheese or some sort of milky soup sometimes add variety to the buffet. The locally brewed beer is the light Druk Lager. This is not the award-winning pilsner you might expect, although what it lacks in quality it does make up in volume. Only 110 Ngultrum for a full 650 ml of light lager with just a hint of petrol aftertaste. (At the time of our journey, 110 Ngultrum = 2 USD.) Enough Druk Lager to wash down the noodles, and then it's time to fall asleep to Star TV while wondering why Indian consumers want whiter underarms and tea-flavored dental rinse. The endless car and diamond ads I get.

Day 3: Punakha

The morning finds us hiking up to a chorten above the Punakha valley. This lovely temple is set above fields and orchards, about 30-45 minutes from the road. It is designed in 3 stories, with a balcony on top with amazing views. Each tier of the temple is dedicated to the same protective spirits, although the use of each level is different. By climbing the narrow stairs up, we have a wonderful view of the wall paintings normally missed at the top of each tier.

After returning to the road, we next return to the Punakha Dzong, now after the festival and much less crowded such that we are able to appreciate both the setting and the size of the building. It is much larger than any other building we've seen -- except perhaps the Taj! -- and even though it is down in the river valley dominates the surrounding area. It is reached by way of a gorgeous covered wooden bridge over one of the rivers. It's a bit like crossing from the normal world into a world of history and perhaps myth. The Dzongs have a strict dress requirement, as all locals must wear native dress and all foreigners must wear long-sleeved collared shirts and long pants or a long skirt. Our travel gear is normally culturally sensitive, but we don't run to collared hiking shirts, so we have stashed a couple of “Dzong shirts” to button on over our regular gear for the purpose. Mine, however, is a rather bright turquoise polo shirt that leads to some rather interesting color combinations. At least it wads up in a backpack rather well.

There are three ladders (really steep staircases) to climb to enter this Dzong. This is not a necessity of Dzong architecture in general, although it is an interesting feature of the defensibility of this particular structure. The inside courtyard is now empty, allowing us an excellent view of the elaborately carved balconies. The central tower looms over the courtyard, and contains a shrine and temple. Beyond the central tower is the working monastery, now busy cleaning up after several days of celebration. The building is a combination of temple and government offices, and the Dzongs make up the administration of the country. Each valley has a Dzong, which serves as a provincial office, monastery, large temple, and festival gathering location for the surrounding area. Even the capital itself is based in a Dzong in Thimphu with the same basic structure.

Our next stop is a nunnery on a hill, originally home to 40-50 young women but now hosting over 100. There is not as strong a tradition of women becoming nuns here as we have seen in other Buddhist countries, but this is one path to education and an alternative to village life that is increasingly attractive to some young girls. The nuns are hard at work making small clay stupas for offerings and the elaborate flour, butter, and water decorations used to commemorate special events and which are found at all altars throughout the country. These are unique to Bhutan, I believe, and are carefully sculpted with tiny balls of dough, some dipped in food coloring, then applied to a plywood base. The finished result ranges from middle school craft project to genuinely lovely, intricate, geometric designs. Todays' examples are in danger of melting in the sun and are quickly moved to a shady spot to complete.

It's worth mentioning the banners and patterns of Bhutanese art. There is a strong tradition of geometric patterns in the five elemental colors, yellow predominating as the color of the Buddha. These often look a bit like a Midwestern quilt pattern, all squares in V-shapes and diamond blocks. The banners are often round, with triangular arrows of different colors in trailing bands, again forming patterns of chevrons as you go around the circle. They are pretty, but really look like there was a Kansas-Bhutan pattern swap at some point.

As we drive back to our hotel/WiFi pavillion, we notice a forest fire on one of the hills across the river. As a heavily forested country with largely wooden buildings, Bhutan is highly vulnerable to fires. The scars of prior blazes are clearly visible on the hillsides, sometimes sadly including the white vertical prayer flags on tall poles that are used in mourning. One of the nearby Dzongs, Wangdue Podrang, was gutted by fire last year, and almost every other Dzong seems to have been restored after a terrible fire of variable chronicity. The written records of the country were lost, several times, due to....fire. It is perhaps understandable that there is a government mandate to have fire extinguishers in every temple, and that butter lamps are now banished to a separate structure and cannot be lit inside a temple. Given that the fire at Wangdue Podrang may have been from an appliance in an office, however, the butter lamp jails may not be sufficient. Tonight we watch the smoke creep closer to homes and worry about the effect of the strong wind on the efforts to contain the blaze. At least one good result of the wind is that the WiFi pavillion is almost deserted. My download of this week's new Economist moves swiftly.

Day 4: Punakha to Thimphu

This morning finds us crossing the Dochu La pass back to Thimphu. There are many tourists there (ok, like a dozen), but it is overcast and nothing like the gorgeous experience we had a few days ago. We move on to take the road to Thimphu. Today is Sunday, and therefore several important landmarks are open for visitors that are normally closed to tourists during the week. We start at the Memorial Chorten, erected in 1974 to honor the 3rd King. There are 5 kings in the modern era, and many sites are dated by renovations or plans put in placed by the 3rd or 4th kings. They are a very hands-on monarchy, and the 3rd king set the country on its path to (relative) modernization. He put in place a 5-year plan to build roads, provide electricity, build schools, and yet preserve all that is special and unique about this corner of the world. He initiated the ideal of Gross National Happiness as the goal for development, and this remains the standard. The 4th king continued these 5-year plans and in 2008 moved to a representative democracy with a constitutional monarchy. After convincing people to vote, he then abdicated to his son, the 5th king. Despite the new Assembly, the kings seem to be the last word and center of much decision-making. They are certainly highly respected.

The Chorten is a square 3-tiered structure similar to the one we saw the other day in Punakha. We cannot climb this one all the way to the top, and it is regrettably dark inside. We can see the large constellation of demon-faced statues in the shrine, facing outward in a circular display. Outside many local residents circle the shrine, sometimes stopping to prostrate themselves on the provided wooden boards. It's actually crowded and busy, a unique quality for us so far.

Our next stop is the Thimphu Dzong, now the center of government for the country. This is laid out like every other dzong in the country, half administrative and half monastery/temple. The administrative half includes the King's offices, several key ministries, and is guarded by royal bodyguards. The King's residence is just a short way down the river, a lovely house with pretty gardens. Across the river, connected by a short bridge, is the new National Assembly building. The Assembly initially met in the main temple of the dzong, but this building was then commissioned to give them a separate space. They are currently in session, so there are colorful flags and bunting around the building. We are not allowed in the administrative section of the dzong, of course, but rather enter a door further down. There is an Xray machine, but other than that the guards as usual seem mostly concerned that we are dressed appropriately. The interior of the dzong is similar to Punakha, but much newer and shinier. The main shrine is large and beautiful, with the usual reserved chairs at the front here holding pictures not of the local lama but of the king, the past king, and the head lama of the country. Other than the illustrious seats, the shrine looks much like others in this country; this is a working building, not a showplace.

We go from this shiny new center of government to one of the oldest temples in the Thimphu valley, Changangkha, which dates from the 15th century. This is a tiny lakhang on a steep hill, crowded today with well-dressed families with small children. We learned that this is a place of pilgrimage for healing sick children. Families come bearing bags of Indian potato chips, soft drinks, biscuits, and bags of uncooked rice. This might seem like an odd box lunch, but in fact these are the offerings to the temple. Each figure in each shrine has a big bowl of chips and crackers in front of it; these were given as offerings, and after sitting on the altar for some time they are then distributed to the poor (or perhaps the monks?). This system is used in other religions and other Buddhist countries throughout Asia, but the preponderance of snack size Magic Masala Lays is unusual in my limited experience. In any case, many very small children decked in thick silks are blessed by the lama. Many are coached through prostrations to Buddha and to the lama's seat, although the children seem to think this is an excuse to perform a dance of their own devising. They are not scolded, just gently guided out of the way with a smile. It is fascinating to see the business of the temple and the comfort these families clearly have there, despite their deep respect for the lama and the shrine. Only men are allowed within the inner shrine, but their wives provide coaching on the proper stacking of Lays in the offering bowls through the door. The children, despite possibly needing blessing for illness, all seem well and happy, no signs of poor nutrition or injury. There are only 147 MDs in the whole country by the last census, almost all Nepali or Indian, and only 1 big hospital, but the population is very healthy by WHO metrics. There is essentially no famine or malnutrition despite the lack of arable land, and there are many tiny health centers scattered throughout the valleys.

Leaving behind the city, we drive up to a small wildlife sanctuary. There are many national parks and the government takes poaching very seriously, but there is only one zoo-like entity in the country. This is a sanctuary for takins, the national animal. Legend has it that they were created from the carcasses of a goat and a cow -- the head of the goat on the body of the cow. That's a pretty valid description of their looks. They are a strange dead end on the mammalian toxonomy tree. These particular takins were supposed to be returned to the wild a few years ago, but they basically refused to go. They hung around town eating crops and rooting through garbage, at which point WWF helped build a small enclosure for them. They also host some injured local animals -- a sambar deer with 3 legs, some other deer with marks of injury. The takins are odd-looking but seem friendly.

The evening finds us back at the amazing Taj, where there are actually four other tables occupied at dinner! Shocking. We have to share our stove. After two days of noodles, excellent Indian food comes as an indulgence that is much appreciated. I even decide to spring for Indian beer and skip the Druk Lager....experience.

Day 5: Thimphu

The day starts, as all days should, with the extensive Taj breakfast buffet. Watermelon juice and actual coffee all around. (The hotel in Punakha made Nescafe with a near 1:1 ratio of powder and water that made the result rather more chewy than even this Starbucks lover could tolerate.) This morning we are hiking up (very up) to the Tango monastery. This is named for the horse's head appearance of the rock where the original temple was sited. It is a centuries-old temple and monastic school, now expanded as more young boys come to study at one of the centers of Buddhist learning in the country. As students are starting the spring term this week nationwide, the path is very popular with young monks. They typically arrive in groups in a taxi, then hike uphill with their mattress, books, and other belongings. There is a winch system in place for some heavy items, but this seems to serve mostly as a moving tripwire as we go up the switchbacks, and certainly the novice monks don't seem to get to use this for their belongings. The monastery is notable largely for its age, and may have been one of those established in a wave of temple-building that drove the dissemination of Buddhism across the country. Although this is one of the main sights in the Thimphu area, we do not see other tourists on our hike, just many moving monks. There is infrastructure in the form of special tourist-only Western toilets, though.

On our way back to town, we stop at the National Library. This is probably not very interesting for most people, but any collection of books is a necessary site for us. There are two buildings, one a large older structure with glass-fronted bookcases of scrolls. These are religious texts, written in Dzongka, and pressed accordion-style between wooden boards, then wrapped in silk. The color of the silk wrapping indicates the topic and school of the writings within. There are innumerable wrapped scrolls stacked on the shelves with several stories of bookcases. Each floor has a small shrine with offerings and prayer wheels. These scrolls can also be found in each temple, of course, but the national library hopes to have copies of all the works in the country for safe storage. Next door is a newer building with English-language books donated by a variety of groups. This looks like nothing so much as the neglected branch of a small-town library, with a very random collection of books that seem to be whatever was donated. There is a full set of the US Supreme Court proceedings from the mid-90s. The Computer Science section includes a few books on Pascal, and the Medicine section is mostly references on Chinese herbals. I almost wanted to leave behind our few reading books, or start a collection at home. Then I realized that eBooks will probably surpass these few offerings rapidly. It's a country that might leapfrog to the next technology, similar to mobile phones taking over landlines. Perhaps in anticipation of this, there is a small digitizing effort underway to preserve the scrolls before the next inevitable wave of Dzong fires.

Lunch is a selection of Bhutanese specialities, which I regret to say have me pining for the tourist-standard noodles. I'm game for chiles with cheese, but the cheese is so pungent and thick that it doesn't make for a pleasant experience. Gummy and yet spicy. The sauteed eggplants are pretty good, but other vegetables seem to come “stewed in cheese sauce”. The soups have a strange base that I can't identify -- possibly simply ghee, water, and flour -- that somehow manages to have both the consistency and taste as Palmolive. More Indian food at dinner is definitely called for.

The afternoon is spent visiting a unique museum of prior farming life set up in an old home. A member of the royal family preserved the farm property and collected all sorts of items from daily life to give an idea how people lived, although the “old days” depicted are only about 30 years ago. There is a snow leopard head handbag (seriously...ears and all...) that is rather horrifying, but the rest is interesting and spare us a visit to gawk at some family's actual home to visualize the workings within the large and elaborately painted houses that dot the hillsides.

We also visit several schools. One is for the 13 designated cultural arts and is set up as a 4-6 year program to train artisans who then can do the woodworking, painting, sewing, sculpture, etc. required to maintain the homes and temples of the country. This is a government funded effort and the graduates are apparently in high demand. Surprisingly, there is no gift shop. The paper workshop nearby focuses on making paper from the pulpy stem of the Daphne plant, the result lovely thin paper with character that seems to take dye well and then can dissolve without pollution. They supply the tourist trade with notebooks and cards, but also local shops with paper bags now that plastic carrier bags are illegal.

To cap our day, we drive up to the BBS broadcast tower, on the highest hill around the capital, to survey the Thimphu valley. Fields are interspersed with small, denser neighborhoods. The few large buildings stand out, including our hotel, and despite the areas of more dense building it looks more like a medium-sized town than a capital city. Cows can be heard and you pass ponies on the roads, in addition to the inevitable dogs. Each stream has a small shrine with a prayer wheel, spun by the falling water, and decorated with flags.

Today is Oscar Sunday, and we were sad to miss the live broadcast, but then we discover that it's being replayed on Indian cable! More good Indian food, good beer, and then Oscar viewing. Amazing.

Day 6: Thimphu to Haa

It's a long morning of driving to get to the relatively quiet Haa valley. This area west of Paro was opened to hiking in the late 90s, but there is only 1 rough hotel with 12 rooms, so few tourists now come this way despite the beauty of the surroundings. That said, we only have seen other tourists some of the time, although the Punakha hotel was full (all 24 rooms) for the festival, the Taj was almost empty. I doubt capacity is an issue at this time of year, and in fact we are the only ones in the hotel tonight. We were placed in room 1, which sounds good but also happens to be the further from the dining room/lobby. Given the chill at night, the distance matters!

The valley is actually more traveled than we expected due to the presence of an Indian Army base and a group of Bhutan Army stations. The Indian Army moved into the local Dzong in the late 60s/early 70s and use it as an HQ, eventually building a whole complex around it. Ostensibly there to protect Bhutan, the reality is that this country sits between India, and in particular Assam, a sometimes troublesome state, and Tibet. They are vulnerable to being used as a staging ground/Belgium by either party. India began to claim their spot by setting up this base in the valley most accessible to them at the time. It also has the lowest pass to Tibet, and the locals walk over frequently to buy cheap Chinese goods; this is obvious given the stacked supplies of cheap polyester blankets, kettles, and thermoses on display at each tiny general store. The Indian army trains the local army and provides expertise in road building, engineering, electrification, water delivery, and other key aspects of development. The proudly note the electrification of the Haa in 1974 as a key accomplishment. The national roads are built and maintained by a private company, Dantak, founded by Indian army engineers who retired to Bhutan. Given all this military activity, you might expect a prosperous little town; sadly this is not the case. The valley is notably less well-off than the others we have visited, with the houses in some disrepair and fewer goods at market. Another contributor is the effect of two recent earthquakes in 2008 and 2011 that flattened the traditional pounded-earth houses. Some others near the riverbed were washed away by flooding. Rebuilding is evident throughout the valley.

The main historical sights of the valley are the Lakhang Nagpo and the Lakhang Karpo, the black and white temples. These were built in the 7th century, and the black temple is reputed to be one of the 108 built by the Guru Rinpoche in his travels through the region. The continued practice of Bonism, the native animist tradition, is clear in these temples as the local deity Chhundu is honored with his own shrine and is provided earthy gifts of beer, Arak, and even animal sacrifices on special occasions. Both of the temples are undergoing repair after the earthquakes, but the main structures are intact.

We retire early to our lodge to get in before sunset and the cold. The Haa is higher than Punakha and has light snow and frost in the mornings. Our room has plumbing, a very robust hot water boiler, a kettle for tea, and two equally enthusiastic space heaters. Although initially pretty cold, after several hours we're able to get the room up to 70 degrees! The bathroom, all tile with a slatted window open to the outside, is a lost and very cold cause. I treat us to a package of peanuts I stashed in my bag in the Bangkok airport. This has turned into an informal altimeter for us, and the package is now ready to burst! Tasty peanuts, though, and we manage to open it without causing peanut projectiles to fire out at us. The Army might have been alarmed.

Day 7: Haa Valley

The Haa valley is known for gorgeous hiking trails. This used to be the site of many short treks, although now as roads are built some of these trails have disappeared. This is a frequent (and rather convenient) aspect of our trip, finding that what was billed as a 6-hour hike is now only 2 or 3 hours long due to road building. More touring for us! This morning's walk takes us through small clusters of houses and their fields, following the river valley. Due to recent earthquakes, many houses show signs of damage and some have been abandoned entirely, the family living in a shed and collecting materials with which to rebuild. As we walk we see many families in different stages of building - collecting stone, wood and other materials, building a foundation, pounding dirt walls, laying floors. It is tiring work that pulls in the whole community, but everyone seems remarkably cheerful as they labor. There are few modern building materials, as the $15-20 necessary to buy concrete for the foundation is outside the reach of most farmers.

As we walk we are often trailed by the inevitable Bhutanese dogs. These are a fairly uniform breed, very smart and probably good farm dogs. Our hotel has three puppies, two black and one beige, who trail Steve and use their big puppy eyes on him, so adorable they just have to be acknowledged each time we pass. One of the challenges to tourism is apparently the incessant night-time barking of the many dogs throughout the country. They do occasionally seem to have a canine disagreement that necessitates very noisy argument, but for much of the night they are relatively quiet. Apparently the barking is complaint #1 from foreign travelers. Personally, I'd list the dubious food, but no, it's the dogs. Such cute little puppies to cause so much trouble.

The Haa is higher and colder than Punakha, and we understand that the pass that leads most directly to Paro, the Chele La, is still closed due to snow and ice. Normally we would cross this pass the next morning, but it looks like we'll have to retrace our steps out the other side of the valley to the “confluence”, the point at which the main east-west road meets one of the larger north-south roads. This is also the point at which the roads to Paro, Thimphu, and the Haa all meet. It's a large intersection -- for the purpose, the roads are actually two lanes wide and they have a few international-style highway signs. We came this way from Thimphu, but were hoping to take the more direct and picturesque Chele La direct to Paro. Since we're going to miss the drive tomorrow, we decide to try to reach the pass from our side to see the amazing views, even though we can't descend the other side.

The drive up is long and windy, but almost empty of cars since there's nowhere to go. Groups of local residents are out collecting wood from fallen trees, picnicking in the middle of the road. Forestry is strictly regulated in Bhutan -- you have to ask permission to collect even fallen wood. I wonder how much of this collection is permitted, but it is at least clearing deadfall from the road, so it does seem like a service. From the road we can now get a perfect view of the three conical hills called “rigsum” that look over the valley.

The pass is the highest road in Bhutan, reaching almost 4000 m. The top of the pass has an unfinished building, apparently originally intended for a restaurant, but then the permission was rescinded by the King. It stands there with unfinished cement block pillars, covered with snow, looking just a bit forlorn. As we look down the hill on the other side, we can see Paro. In fact, we can see the airport and even spy a plane coming in for a landing. As we hike around the top of the pass, we can even see the famed Taksteng monastery in the distance. We had no idea that we were so close! Unfortunately, we can also see why this pass still isn't open -- only a kilometer or two down the road, we can see switchbacks covered in snow and ice, clearly not yet passable.

In order to make the most of the drive, we climb up the hills next to the pass to reach a small stupa at the original pass location, still in use for a footpath, and then further up to a small rise from which we can see both valleys. The snow ranges from several inches deep to over a foot, and although the dropoff isn't too steep, there is the unpleasant possibility of sliding rather a long way down before finding anything to hold. We wade through drifts and keep climbing. It's all worth it, though, to experience the clear blue sky, the pristine snow, the sound of the prayer flags whipping in the wind. For just a moment you can be alone on top of the world.

Day 8: Haa to Paro

Today we take the road more-traveled back to the “confluence”, and from there to Paro. On the way, we stop briefly at a small building, previously used as a Dzong, then as a prison, and now being converted back to a monastery. Like many Dzong it is in the river valley, but this one is constructed on a headland with steep drops on 3 sides. This apparently made it a good choice for a prison for those criminals sentenced to life. The prisoners have moved on (to where?), and the building is now under construction for its more peaceful purpose. After a brief exploration we head on to Paro valley itself.

In addition to the airport, the Paro valley is the site of several key monuments. One of these is the National Museum, formerly housed in the hexagonal watchtower above the Dzong. This watchtower is a construction marvel given it's age, dating to the 17th century. Unfortunately it was also damaged by earthquake, and the collections have now moved to a modern building across the street. The museum houses a collection of thangka, some dating back to the 16th century, that have been collected from temples throughout the country and preserved. The artistic styles of painting vary significantly, with some showing a clear Chinese influence and others appearing to have scenes direct from the Ramayana. The museum also houses collections of the dancing masks used in festivals, although these are all new and chosen to represent the different characters rather than preserve the old wooden masks. There is also a display of wildlife that is long on posters and videos and short on actual wildlife. There are two taxidermy snow leopards guarding the entrance, and a few boxes with preserved birds pinned to a central pole.

After the museum, we hike downhill to the Paro Dzong, one of the oldest in use as it also dates to the 17th century, and also one of the most formal. It sits next to the river with a stunning wooden bridge leading to it, or it can be reached by the hill we are descending. We pull on our rather bedraggled collared shirts to find truly stunning painting and carving behind the doors. This Dzong has the usual central tower, the courtyard, and the outer periphery of lower buildings to form a rectangle. It also has a number of small temple rooms on either side of the courtyard, framed with new murals of the life of the Buddha. These smaller temple rooms have gorgeous views of the valley below and of the monasteries on the hills above; even more so than in Thimphu, the Paro valley is a strung-out collection of small villages and farms connected by the river and a road.

This evening we are staying in the amazing Zhiwa Ling hotel, the first Bhutanese-owned luxury hotel in the country. It is a monument to traditional crafts, and the main building is like a colorful museum with carved and painted columns throughout, murals on every wall and ceiling, and local artwork throughout. The door pulls are braided white scarves, typically used in greeting much the way leis are given in Hawaii. The entryway houses lovely murals of Buddhist themes, and the Four Friends preside over one half of the dining room. The rooms are gorgeous, although not as ornate, and seem to have a high percentage of local woodwork mixed in with the Indian fixtures. The setting is equally lovely, on a patch of land far enough away from the central part of the valley to be quiet, the rooms set in small bungalows in a U-shape around the main building. There is a meditation lodge, a tea room, several greenhouses, and a fitness area/spa, all in small buildings scattered on the hillside. The restaurant grows much of its own produce, and the menu, although limited, is delicious. It is a treat to be in a such a gorgeous setting, and even more so to feel that you can help local entrepreneurs take advantage of the tourist market. Perhaps given the extraordinary setting, there seem to be a few other guests here and we actually have to share the dining room with two other tables! Shocking. After the very good but rather basic food in the Haa, a nice Indian thali hits the spot very well. Unfortunately I decide to try the other local beer, Red Panda. It comes in a large bottle that has “King Lager, do not reuse” molded into the side. The label is askew, and appears to have been printed on a 5 year old HP laserjet printer. Apparently this is an unpasteurized (!) white beer from Bumthang. Now, I've partaken in quite a few local beers throughout the world during my travels. Some have been more...chemical...than others. I have never previously found one that I couldn't finish. Congratulations, Red Panda lager, you have officially broken my record. There was an unpleasantly bitter initial taste that was followed up by a distinctly phenol-like aftertaste that also somehow managed to conjure up images of licking tires. I just couldn't do it. The Red Panda will remain endangered, more so if it comes across any bottles of its namesake. The lovely thali and a soft, warm bed make up for all such problems, however.

Day 9: Paro and Taktsang

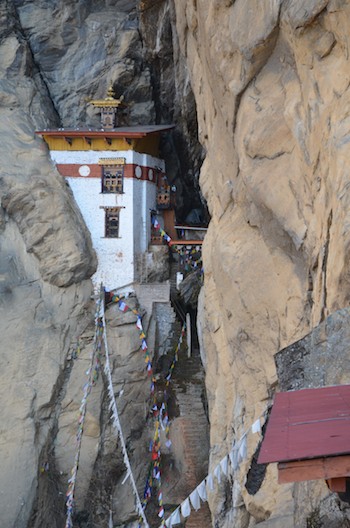

We wake early today to start the half-day hike to the famous Taktsang (Tiger's Nest) monastery. This is the iconic image of Bhutan, the white-walled monastery clinging to a cliff-face, seemingly inaccessible save to birds. From the trailhead 700 meters below, we can see a smudge of white and some red roofs, just enough to believe that it's really up there. On the surrounding hills there are many dots of white, these being small temples and meditation rooms associated with the temple, as well as some stupa and shrines along the path. We had gotten a vague glimpse of Taktsang from the pass two days ago, and another slight view from the hotel last night, but there's nothing quite like looking rather far straight up to really bring home the morning's task. Still, this is the pinnacle of Bhutanese tourism, as well as one of the holiest sites in the country. Fortunately for us, the trail head is now some hours closer to the monastery thanks to the constant road building throughout the country; ten years ago this was an all-day event, starting not far from the site of our gorgeous hotel!

We have hardly left the car park when we come upon a small medical emergency. There are some (mostly) domesticated ponies that the locals hire out when they aren't needed on the farm to transport tourists most of the way up the hill. One of these ponies took offense to its new rider and promptly reared, causing the wooden saddle to come into abrupt contact with her face. She slid off and fortunately avoided being kicked, but she had some pretty substantial bruising and soft tissue injury to her forehead and cheek. The local guides and pony providers were standing around fussing over her, but without much effect other than to provide her bottled water. I unfortunately didn't have too much with me, but my standard hiking kit does include alcohol wipes, Neosporin, a good flashlight, some eye drops, and a few other useful bits. Thanks to many deities, her eyes and teeth were intact, but it took some cleaning to ascertain that she probably didn't need any stitches. I helped as I could and she gamely remounted, but it must have hurt. I suspect she spent the next week of her trip through Nepal and Burma eating soft purees and drinking lukewarm water, cursing mountain ponies under her breath. A somewhat traumatic half hour after starting out, we regained our backpacks and tried again. No more ponies! (As an aside, our travel agency actually forbids guests from riding the ponies due to the number of accidents and injuries that they can cause on the steep mountain trail...I'm not surprised! Given the closest local physician is a couple of hours away, and the closest trauma center several more hours by helicopter in India, it seems that avoiding them is a good idea. Important travel tip.)

We climb up...and up...and a little more up...the dirt trail, switchbacking through the pine forest along the side of a mountain. It is warm, no snow in sight, and we are grateful for the shade of the trees. From time to time the trail opens out into the sun and it is definitely clear that there's a lot less atmosphere protecting us from UV rays here than in Boston! About ⅔ the way up there is a small cafe catering to the footsore and breathless, as well as to those who like a little plumbing in their hike. We press on as the path narrows. Along the way there are several small shrines, some associated with streams. The streams often are set up with a paddle-wheel system that turns a prayer wheel set in a shrine above. As with most prayer wheels, there are bells that chime each time the wheel makes a full rotation. The stream merrily jumps down the hill, slowly turning the paddles, and the bell sounds from time to time as the wheel goes full circle. It's a wonderful system and adds to the natural splendor of the forest, combined with the white shrines and the ever-increasing number of prayer flags, both vertical and horizontal, that drape the hills and the shrines. As we get closer to our goal, there are more frequent sightings of small white buildings on the hill above us, partially hidden in the trees, but visible due to the flags that fly from their roofs. The path is sometimes draped in arches of flags, particularly at a sharp corner from which you can finally see the monastery itself in its full glory. It has been teasing us for hours, partially visible at times, sitting up above us. Now as we approach the same height we can finally see more than a smudge of white.

There is a viewpoint and shrine at the edge of the path, so heavily draped in flags that you have to duck and weave to get to the edge to see across the ravine. From here you can see, almost at eye level, the entire Taktseng complex clinging to the hill. At first it's unclear how you get from here to there -- zipline? -- just as it's difficult to understand how the many ropes of prayer flags have been draped across the ravine. There is a steep staircase leading down, then a bridge that crosses in front of a waterfall, then another short staircase up to the entrance of the monastery. Throughout the descent and climb I have to stop every few feet, not short of breath but amazed at the constantly changing views of this miracle of engineering. The light is slowly reaching this side of the hill, and although the waterfall remains in shadow, the monastery is now in the light, gold roof decorations glinting brightly in the sun. It's a good thing we went digital a long time ago, or I clearly would have run out of film in this short stretch! Unfortunately a few of our fellow travelers were not able to make the crossing due to vertigo. The path up to this point had been relatively wide and the dropoff not too steep, with friendly forest along the way. At this point the stairs and the bridge are pretty obviously clinging to the side of a cliff, and the spray from the waterfall doesn't make them seem any safer. A few choose to sit at the shrine across the way and think earth-bound thoughts, sadly missing the monastery itself. It's an unusual day for us, surrounded by other tourists from multiple nations, and it's almost disconcerting to run into people as we climb. We reach the monastery with a huge group -- perhaps as much as a dozen people! -- and it seems like a crowd after our solitary period in this country.

Once we reach the monastery, we have to carefully prepare before entering. On with the collared shirts, just as at the Dzong. Our cameras are locked up, and our hiking poles and bags left behind. We continue on with our shoes (although we essentially take them off and carry them the whole time) and our clothes, little else. Our guide has to change from sneakers into leather shoes for the visit, although he too will carry them most of the time. The guides, drivers, hotel staff, and all other tourist-facing roles in Bhutan are required to wear national dress at all times, including shoes. Everyone must wear native dress in schools, government offices, Dzong, and to any official event. The native gho and kira are certainly well-adapted to the terrain, and at this point most adults grew up wearing them, but you do wonder what will happen in 10-20 years when children will have grown up wearing jeans outside of school. We had a similar question 6 years ago in Burma, when we noticed almost everyone in native dress and women sporting traditional yellow paste on their cheeks, even in Yangon. As Burma opens up to the west, that wonderful tradition may be lost. The Bhutanese government seeks to avoid a similar fate; but does that really mean that you have to lug formal shoes up a mountain?

In any event, we prepare appropriately and pass inspection by the rather stern looking-guards. Though really, who can blame them for being stern when they have to hike up 700 meters to work every morning? The monastery itself is, not surprisingly, a warren of small buildings connected by tiny courtyards and short flights of stairs. Some of the temples are barely the size of a smallish bedroom, so crammed with offerings and ceremonial bowls that you are hard-pressed to find a place to stand. As is all too frequent a theme, some of the temple was destroyed by fire in the mid-90s. Many of the treasures were saved, and are now back in place in restored rooms, but some were sadly lost. Some of the figures are clearly newer, including some gigantic Buddhas whose presence up this mountain defy understanding. One room features a small meditation hole, in which monks may spend days, months, or even years sitting in a small cave in the dark under the floor of the temple. Just in case living on the side of a cliff was insufficiently isolated for you. The rooms here are all odd-shaped and jumbled, unlike the typically rather ordered design of land-based temples. Despite the rather cramped tour, and despite being with other people for the first time in many days, the isolation and calm of this place is pervasive. Sitting for a moment at the edge of the temple, looking down at the valley below, feeling the wind rush past, you connect with nature and with your own introspection. It is magical, not least for its construction, and is deservedly famous.

The path down to civilization is swifter than the climb, but it is too tempting to stop from time to time to look back and see the Taktsang slowly recede from view, the sun now having moved away, the roofs once again in shadow. It's like descending back to reality. Complete with footsore Taiwanese and the return of the deadly ponies.

After a brief stop for lunch at the wonderfully named “Yak Herder's Rest”, where we were back to our norm of being the only guests, we drove on to the literal end of the road at the other end of the Paro valley. Here we found the ruined Drukyul Dzong, named after the Thunder Dragon from which the Bhutanese name for the country also is derived. This was originally built in the 17th century to celebrate a defeat over the Tibetans, and clearly had an originally defensive purpose.

There are tunnels for escape, channels that can become moats, and it is once again built onto a headland with few access points. It was...you guessed it…destroyed by fire in the 1950s. (Maybe they shouldn't just put those butter lamps in separate buildings, maybe they should put them in an entirely separate country!) This now ruined Dzong has been taken over by grasses and trees, but the fundamental structure and outline remains. It is a beautiful place, stark and lovely if a bit hazardous to climb around. We enjoy our walk around, but notice that one of the very high-end hotels is setting up a dinner event here, complete with bonfires, a dining tent, and some very comfortable looking throws to keep the guests warm after dark. With only a little jealousy, we leave the Dzong to the caterers and return to the road. The paved road stops here, becoming a dirt track that very rapidly peters out to a foot path to Tibet. The road works crews are madly widening the paved road from Paro, and they are clearly already marking out the new roadbed further on. Come in 10 years and this will likely be a restaurant and way station on the way north, instead of an isolated spot among farms.

There are tunnels for escape, channels that can become moats, and it is once again built onto a headland with few access points. It was...you guessed it…destroyed by fire in the 1950s. (Maybe they shouldn't just put those butter lamps in separate buildings, maybe they should put them in an entirely separate country!) This now ruined Dzong has been taken over by grasses and trees, but the fundamental structure and outline remains. It is a beautiful place, stark and lovely if a bit hazardous to climb around. We enjoy our walk around, but notice that one of the very high-end hotels is setting up a dinner event here, complete with bonfires, a dining tent, and some very comfortable looking throws to keep the guests warm after dark. With only a little jealousy, we leave the Dzong to the caterers and return to the road. The paved road stops here, becoming a dirt track that very rapidly peters out to a foot path to Tibet. The road works crews are madly widening the paved road from Paro, and they are clearly already marking out the new roadbed further on. Come in 10 years and this will likely be a restaurant and way station on the way north, instead of an isolated spot among farms.

We drive back across the Paro valley to our last stop of the day, a small 7th century temple nestled among the farms of the oldest part of the valley, not far from the Dzong. As we travel, we pass the airport, somewhat bizarrely crammed in between fields and terraces. It seemed ridiculously tiny when we first arrived, but now the expanse of runway and the large terminal building seem huge. The security consists of a barbed wire fence along the road, separating the runway from the fields, and a single entrance with a few guards. Some of the local cows browse next to the fence, unconcerned. Just beyond the airport and Dzong we find that the temple is open, fortunately for us. This is a working temple, not usually on the tourist agenda, so we have to visit quickly before the next scheduled round of prayers. One of the rooms just off the main prayer room is a small bedroom that was for a high lama. He lived here for a time, although he also had a temple in Tibet. He died a few years ago and his bedroom has been kept pristine, his photo in his seat and his bed in the corner freshly made. The temple is quite old, with worn floors and old, darkened paintings on the walls covered in yellow cloth. The style is very Chinese to the uneducated eye, highlighted with thin lines of gold here and there. The writing is Dzongka, the local dialect, very elegantly scribed among the figures.

Tonight we return to the stunning Zhiwa Ling, determined to take some photos of this gorgeous place before sundown. Another thali, this time with imported beer (sorry....) and then it's time to watch FoxMovies and pack. A quick glance at the hill and you can almost convince yourself you can see the Taktsang high above, keeping watch.

Day 10: Transit Redux

The long road home beckons. First to the Paro airport, now gigantic in comparison to the local landscape, but really just a few rooms and a door to the tarmac. Our duffels are Xrayed and marked in chalk, then checked in. Immigration is confusing, as apparently after you go through you can still come and go as you like if you need to go to the Bank or if you forgot something in the parking lot. Everyone waves and smiles, and it's certainly true that the planes are small enough they could recognize everyone on sight. A few hours, with a stop in Bagdora, and we are back in Bangkok. The experience of the very efficient and friendly Bangkok airport after 10 days in Bhutan is overwhelming -- there are too many lights, too many sounds, and everything moves too swiftly. The promise of larb and satays is more than enough to get us moving, though, and we soon find ourselves happily checked in for our flights to the States, immersed once again in the Thai Airways transit lounge of happiness with plentiful cold drinks, hot food, BBC News, and free WiFi. A small foray to duty free to bring gifts back home (our Bhutanese purchases amounting to roughly $10 of artisanal paper notebooks), and after a nice long wait it's off to Incheon.

We connected via Incheon to a flight on Asiana Air, a 5 star Skytrax airline that we had never flown prior to this trip. We were in the “Quadra Smartium” business class seats, wonderful sleep-flat pods with lots of video options and a little ottoman for your feet. As much as we enjoyed these, and the bibimbab, on the flight over, they are that much more welcome now. Unfortunately about 11 hours into the 14 hour flight comes the unwelcome overhead call “Are there any doctors on board?” Pausing in hopes of a code team does little good and I wind up responding. Fortunately the patient was basically fine, suffering a likely viral gastroenteritis that had caused her to spend the last 8 hours in a certain amount of misery, but nothing life-threatening. Unfortunately the trans-Pacific medical kit seemed to consist only of little sachets of pills labelled in Korean with only “30 mg” written in Western letters. Not helpful, thanks. My handy personal medical kit once again came to the rescue, although there wasn't that much to do, and I exercised my minimal power to get the poor patient a wheelchair and expedited immigration and security. The language barrier between me and the very pleasant but not entirely fluent cabin staff led to an exchange of notes being hurried off to the cockpit, and I can only speculate about what may have been relayed to O'Hare ground control! At least by the time they called me we were over land... All seemed well in the end, although after the pony in Paro and the sachets of untranslatable medications I have resolved to take a much larger medical kit on my next venture abroad.

Home again, filthy duffels and hiking boats in tow, once again in mild culture shock. As we go through the mail and return to our computerized, modern lives, the tempo and focus of life in Bhutan fades rapidly. There is something truly wonderful about the emphasis of happiness, tradition, and culture that has guided the development of this tiny country. It is a unique corner of the world that is striving to retain the things that make it special, but at the same time has been invaded by cell phones, satellite TV, Lays Magic Masala chips, and cheap Chinese blankets. It feels a bit like a small town, as everyone seems to know everyone else and the sense of community in each valley is strong. The distances are deceptively short -- you might be able to see the Paro airport from the pass, but even if the road was open it would take a couple of hours to get there. India and China stare at each other across the mountains, and presumably if the monarchy were not so stable it would be a second Nepal, a pawn for their territorial games. It seems unlikely that Maoists or guerrillas will somehow take over these peaceful hills, just as the idea of a Bhutanese army with guns instead of arrows seems almost comic. Still, the world changes, and just as roads are spreading throughout this country so fast that the tourist brochures can't keep up, so too will the outside world continue to intrude, even in 10 room guesthouses. May Taktsang continue to look down on the valley, pristine and intact, keeping the center in place.